(Photo by Ed Robertson on Unsplash)

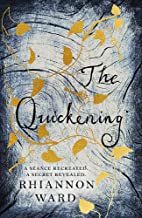

I love a gothic mystery, and The Quickening by Rhiannon Ward (Trapeze) had me gripped. Set in the 1920s, the narrator, a heavily pregnant photographer, is sent to a decaying old pile in Sussex to photograph the contents for auction. But the house was once the scene of a dramatic séance, which is about to be recreated.

My first job in publishing, way back in the mists of time, was on Macmillan’s thirty-volume Dictionary of Art, so I was naturally drawn to Eley Williams’ terrific debut novel The Liar’s Dictionary (Heinemann). It’s ostensibly about the search for fake entries (‘mountweazels’) in an unfinished encyclopedia, but is also a witty love story and a celebration of the power of language.

Caoilinn Hughes’ The Wild Laughter (Oneworld) is a tragi-comic story of two brothers trying to deal with their aged father’s dying wishes in post-boom Ireland, while Anna Vaught’s excellent debut novel, Saving Lucia (Bluemoose), tells the story of the unlikely friendship between the Hon Violet Gibson, who attempted to assassinate Mussolini in 1926, and Lucia Joyce, daughter of James, after they were both deemed mentally unstable and sent to the same institution.

I had never read any of David Constantine’s work before, but his latest collection of short stories, The Dressing-Up Box (Comma Press) left me wondering what had taken me so long. Weird in a very good way, the opening story, in which a group of children barricade themselves in an abandoned house, has haunted me ever since I read it. Annabel Banks’ debut story collection, Exercises in Control (Influx) also stood out.

Despite barely having left the house since March, I was asked by the Sunday Times to do their round-up of the year’s best travel books. There were several gems, but two really stood out. The Lost Pianos of Siberia by Sophy Roberts (Doubleday) is partly a treasure hunt – Roberts was asked by a Mongolian friend to find a piano for her in Siberia – but it’s also a tremendous account of that region’s history and culture, taking in Rasputin, the gulags and the last tsar, among many other wonderful things.

For several years Gareth Rees has run a website called Unofficial Britain (www.unofficialbritain.com), which collects strange stories about places that tend to get overlooked: car parks and flyovers, motorway service stations and tower blocks, industrial estates and power stations. His book, Unofficial Britain: Journeys Through Unexpected Places (Elliot and Thompson), sees him travelling the country in search of more such tales, including the exploits of the Grimsby Ghostbusters, called to deal with a slew of supernatural happenings in the coastal town. These are examples of the new British folklore, he argues, every bit as valuable as the myths and mysteries that swirl around our older buildings and landscapes.

I read some great books this year that were actually published in 2019 and so should technically not appear here, but what the hell – blame it on the pandemic. The Complex by Michael Walters (Salt) is a superbly unsettling, dream-like novel about two families coming together and falling apart in an isolated house, while Ian MacPherson’s Sloot (Bluemoose) is a very funny Celtic screwball noir about a failed stand-up comedian who returns to Dublin for a funeral and gets caught up in a crime caper.

I’m a recent convert to flash fiction, both in my writing and reading, and two collections showcased some of the best examples of the genre: Some Days Are Better Than Ours by Barbara Byar (Reflex) and Ken Elkes’ All That Is Between Us (AdHoc).

I loved Toby Litt’s Patience (Galley Beggar). Set in an orphanage, it’s narrated by wheelchair-bound Elliott as he observes the daily dramas of his fellow orphans and their carers. Elliott is one of the funniest and most engaging narrators I’ve come across in a long time, and if you want to discover the rules of a game called Sockball, this is the novel for you.

My overall book of the year is Susanna Clarke’s brilliant Piranesi. I loved Jonathan Strange and Mr Norrell and my hopes for her new one were very high. I wasn’t disappointed. Piranesi lives in a house of seemingly endless rooms, filled with huge statues, and with a lower floor inundated by the sea. Every week he meets up with a man known only as the Other. Where is this place? Why are they there? Mysterious and fantastical, it’s a stunning novel.